‘Migrants have been beaten, hounded by dogs and burned with cigarettes’ – on the frontline of the Poland-Belarus border crisis

Published on: December 3rd, 2024

Read time: 13 mins

Joanna Klimowicz is a journalist who has reported extensively on the crisis at the border between Poland and Belarus. This article is an expanded version of a talk she gave at the recent ISRF Conference. It was produced in collaboration with Adam Smith (Universal Impact).

Unidentified bodies lying in the woods. Border guards beating and robbing refugees. Families loaded into the back of lorries and transported across borders, their fates unknown. These scenes might be more commonly associated with the atrocities carried out during the Second World War, but this is not the case in this instance. What I’m referring to is a systematic breach of human rights which is being perpetrated in the heart of Europe during the 21st century.

I’ve covered the humanitarian crisis at the border between Poland and Belarus for more than three years, starting in the summer of 2021 when I was working for Gazeta Wyborcza, a major opinion-making newspaper. In July of that year, we first noticed families trekking through the woods with their luggage, many carrying suitcases and wearing flip flops. This terrain isn’t easy to traverse at any time of year and these people weren’t prepared for what was ahead of them – they’d trusted human traffickers who told them it’d be easy to make it over the border, to safely enter Europe, to travel on and be reunited with their families in Germany, passing together beneath the Brandenburg Gate.

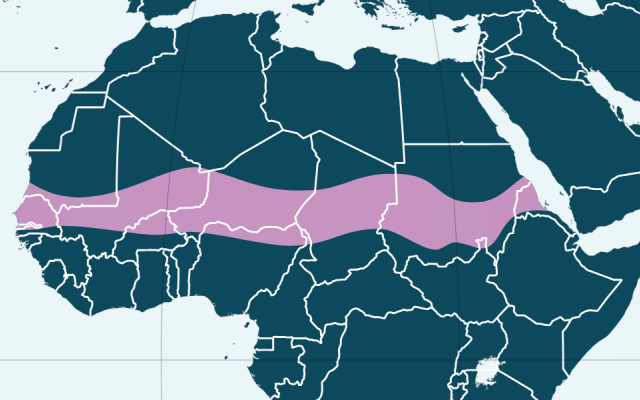

This is part of a campaign of hybrid warfare initiated by Belarusian dictator Alexander Lukashenko, with the assistance of Russia. The aim: to destabilise the European Union, creating pressure by artificially generating migration, turning desperate people who are looking for a safe life into weapons. Belarus encourages those who’d otherwise find it difficult or impossible to get a visa to come to Minsk by plane. Once in Belarus, they’re taken to the border and allowed to travel into Poland. When they reach the “death strip” – the forested borderland between the barbed wire of Belarus and Poland – their fate is no longer in their own hands. This operation was launched in response to EU sanctions imposed on Belarus after the rigged presidential elections in 2020. It’s also a business opportunity for Lukashenko. The journey to Europe costs up to several thousand US dollars. Whole families pool their resources in the hope of starting a better life in Europe, selling property and belongings, taking out loans.

Polish border guards caught migrants and refugees who managed to cross the border. No one questioned it: the borders needed to be protected. It seemed Poland was helping these refugees who had travelled from Syria, Yemen, Iraq and were now requesting protection. It was assumed that procedure would be followed, they’d be placed in the relevant centre. Naively, we thought there were appropriate regulations in place, the Polish Constitution and international law as laid out in the Geneva Convention, and that these would be respected. But soon, we noticed these people weren’t provided with food or having their wounds dressed. They were just put in the back of lorries, returned to the border and pushed back into Belarus. The Belarussians responded to these pushbacks with such cruelty. They’ve stolen money and belongings. Migrants have been beaten, hounded by dogs, burned with cigarettes, raped and pushed into Poland. There’s been brutality on both sides of the border and, throughout the crisis, the violence has escalated.

The first time I realised the extent of the situation was three and a half years ago, around the time of the withdrawal of US forces from Afghanistan. I became aware of a group of around 32 people from Afghanistan, men, women, and children. There was a family with a grey pedigree cat which they’d taken with them on this perilous journey. This group was living on the border – refused entry into Poland and unable to return to Belarus. They were held in place by soldiers on either side, living under the rifle’s barrel. For weeks, they stayed in the same place. It was cold at night, they didn’t have access to food, water or medical supplies. They had to drink from a pond, though the women hardly drank at all, rather than experience this terrible humiliation in front of the men.

Agnieszka Holland’s film Green Border dramatises the crisis and is largely based on the journalism of Gazeta Wyborcza, with some scenes directly mirroring reporting from the time. When I went to the border, I wasn’t told how to cover this story, I was free to work on my own terms, collaborating with a photographer, Agnieszka Sadowska. We worked with dedication, often without sleep. At the time, no other local media outlets were present, with many journalists covering the situation using official statements from the border guards, they didn’t bother to dig into the story – as a profession, we didn’t do very well. Our ability to hold the authorities to account was hindered due to a zone of exclusion which was established and remained in action until August 2022, prolonged illegally, in violation of the law and the Polish Constitution. As reporters, we faced the challenge of whether to enter this closed zone, risking punishment for doing so.

When someone else’s health and life was involved, I made the decision to break the rules and enter this zone. First of all we are human beings and then we have our professional roles as journalists. Anyone who’s experienced the situation at the border would realise that when human health or life is endangered you cannot stay objective, you forget about your professional role and just go and support the activists who are trying to reach those in need of help. We comforted refugees and migrants and we gave them hot tea, soup and a sandwich. Activists and journalists would remove their own clothes and give them to people who were soaked and couldn’t move anymore because we were aware that in an hour we’d go back to a warm home and a shower, while a long and perilous journey awaited them. For me, there’s no opposition between being a journalist and an activist because when I report what I see I verify the situation and pay due diligence. In my professional career of nearly 25 years, I’ve taken pride in being reliable and honest – I’ve never had a single court case against me.

We initially believed we could stand up to the border officials and help these people but it quickly turned out that this wasn’t the case. I count myself lucky not to have been arrested, though many of my fellow journalists and activists have been. Photojournalists have been pushed to the ground, and had vulgarisms screamed at them. We’ve been persecuted by both law enforcement and politicians, we’ve been called Putin’s servants and accused of participating in human trafficking. Going to the forest is unpredictable because the authorities make meaningful action so difficult. During one humanitarian intervention we spent six hours in the cold with no internet access as the border guards interrogated activists and journalists. A team from a Franco-German television station Arte got lost while making a video, they entered the zone of exclusion by accident, were held for 24 hours and had to spend the night in jail. All of their equipment was taken and they were banned from returning. After taking the case to court, they were given compensation. However, these kinds of cases became more and more common and we began to lose our trust in the authorities. Still, I wanted to be a credible journalist, to hear both sides and to understand the perspective of the authorities. However, when I questioned the border guards, their answers were pure lies. I was told lies from national and local spokespeople. The most common one was that people who were pushed back didn’t want to apply for international protection in Poland. Many times, I’ve seen people asking, begging, kissing the feet of the border guards and crying: “No Belarus! We want asylum in Poland” – but they are simply ignored.

September 2021, in front of the border guard station in the town of Michałowo, a group of around 20 Iraqi Kurds tried to resist the pushback, explaining why it’d be dangerous for them to return to Belarus and the fate which awaited them if they did; there were bodies in the woods, they didn’t want their children to die there. There were nine children in the group, one was an infant in her overalls dirty from wandering through the woods, she wasn’t even a year old. We made a video with them, my hope was that we could help make these pushbacks illegal. But eventually, they were returned. The horrible ping pong between Belarus and Poland continued.

There were others including Syrian refugees who were so tired they were almost frozen to death. One man was in the late stages of hypothermia. It was the first time in my life I’d seen someone dying in front of my eyes. Volunteer doctors arrived and administered fluids before wrapping him in a silver foil blanket to raise his body temperature. The group were taken to hospital. However, when an ambulance is called, the border guards come too – and they don’t seem to take into account anyone’s situation. Only a few hours on from this extreme health crisis, they were all taken from the hospital and pushed back into Belarus, even the man who had been dying from hypothermia. I still find it difficult to believe that the Polish authorities are able to do such terrible things.

The most shocking moment for me was the death of a Kurdish woman, Avin Irfan Zahir. At 24 weeks pregnant, she’d come to the border with her family to try and find a better life. Because of the severe circumstances, the baby died inside her. She was suffering, her family contacted activists and an ambulance was called, but it was really late. After two weeks in hospital, she died. Her body was returned to Kurdistan and her unborn baby was placed in a tiny white coffin and buried in Poland. He was laid to rest next to other refugee graves in Bohoniki, a village known as the home of the minority Tatar community, which used to be popular with tourists before the crisis. There’s an old Muslim cemetery there which has started to grow again with the graves of people who have died at the border and in the woods.

Joanna Klimowicz at the ISRF Conference in Warsaw, October 2024

Journalists have been working with volunteer humanitarian emergency services to try and document the number of casualties. I’ve recorded more than 60 deaths at the border between Poland and Belarus. This figure rises to around 130 when the borders with Latvia and Lithuania are included, as in the EU-funded report on the crisis called No Safe Passage. There are unnamed bodies lying in the forest, a situation which can only be described as deeply indecent. They deserve to be buried, their families deserve information so they can mourn the death of a loved one.

Podlaskie Voluntary Humanitarian Rescue Service organises searches for those who remain unaccounted for. The police don’t do it, it’s down to activists and volunteers. The state has left us completely alone with this situation. In February 2023, we were looking for a person within a nature reserve in Białowieża Forest. This person had gone missing a couple of weeks earlier so we were pretty confident that we were looking for a body. Using methods of naturalists who work in the forest, we moved in lines a couple of metres from one another, looking carefully. We found another person who we weren’t looking for, a young man from Ethiopia who’d been lying there for a long time, though it was difficult to identify him as his body had been partially eaten by wild animals. It was a shocking sight and one I’ll never forget. We’re civilians, ordinary people, we haven’t been prepared to see human bodies in a wood where we’d usually go for a walk or to pick mushrooms. It’s undeniable that seeing the crisis up close takes a toll on activists and their families. I’ve relied on the support of a psychologist and psychiatrist to deal with what I’ve seen. Not long ago, I attended the funeral of one of my colleagues, another became sick and only recently regained full health.

While much of this was to be expected from the authoritarian Law and Justice, a right-wing populist party, we were shocked when it continued under the new government, the democratic opposition which took office in December 2023. With the change of government, we hoped that human rights, international law and domestic law would start to be observed. However, to our disappointment this didn’t happen. We still see pushbacks. And the current government has introduced a law which decriminalises the use of firearms by border guards in self-defence. I fear this gives them carte blanche to shoot people without consequences. This law was introduced following the death of a 21-year-old soldier who was stabbed trying to prevent migrants entering the country. Though to be honest, the only threat I’ve ever felt at the borderland was from aggressive, masked representatives of Polish authorities who never even bothered to introduce themselves.

While migration involves challenges, it can be an asset and a benefit, but here we’re dealing with a legal and humanitarian crisis. I understand European societies have fears around the threats which might be posed by migration. I appreciate the desire to protect the borders, I’m not saying they should be completely open. However, the policy of pushbacks does not guarantee control – we simply have no idea who will eventually, after many attempts, manage to cross the border and get to Europe. Poland needs to develop a better strategy. Migration cannot be avoided so we should prepare for it.

People need to be treated as human beings. This begins with making sure they have the right to start asylum proceedings. All of this coincided with a crisis in my own personal life with my mother becoming sick and requiring constant support. I had to quit my job at Gazeta Wyborcza to care for her. I’m currently involved with the independent Youtube channel and website Czaban Robi Raban, to my mind the only consistently reliable source of information on the crisis. I’m dealing with the trauma of what I’ve been through but if I could I’d go back to the forest. I remain in contact with my friends who continue to provide assistance to people. We’ve also stayed in touch with families of the victims, often organising burials. These Muslim funerals are attended by people who have settled in the region after fleeing their own countries, Chechnyans, for example, displayed by the war with Russia. Here we see an example of coexistence, different religions and traditions living side by side. Finally, in death, these refugees find acceptance.

See also...

Feature image by Joanna Klimowicz.

Conference image by Marcus Hessenberg.

Bulletin posts represent the views of the author(s) and not those of the ISRF.

Unless stated otherwise, all posts are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.