Feeling Good, Not Bad

Published on: February 5th, 2025

Read time: 9 mins

I remember when I thought that the 2020s would be a decade of rejuvenation.

The Covid-19 pandemic had been terrible, but it unleashed the powers of massive public spending and this held lessons for the climate crisis. But that possibility was stamped out fairly quickly.

What is the larger pattern we’re stuck within? Outside of some big improvements that always come up—China’s remarkable reduction in mass poverty, advances in information and communication technology, the falling cost of renewable energy—the 21st century has been defined by brutal headwinds.

This is a not a pleasant list, but bear with me.

The world will breach climate targets that it failed to set for decades. It continues to fool around with competitive manoeuvring, and has never generated funding that is remotely adequate to the problem.

The response to the 9/11 attacks became a Thirty Years War in the Middle East, which has been joined by the Russian invasion of Ukraine and externally-funded civil wars in Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo and elsewhere. Meanwhile, internal repressions and corporate dispossession generate a steady stream of refugee crises.

The Global Financial Crisis led neither to the meaningful definancialisation of the global economy nor to much of anything in the way of reform. Absurd levels of inequality continue to increase.

There has been nonstop backlash against any and all equality movements even as the post-1980 inequality boom has seriously damaged democracy. Equal pay for women, trans rights, racially proportionate university admissions, refugees from failed states, redirecting some police funding to community medical services–you name it, there’s been a 21st century freak out against it.

The success of massive state action during the Covid-19 pandemic was systematically buried by a political debt backlash, which has now restored fiscal austerity.

The international knowledge system is permeated by unprecedented levels of disinformation, fraud and aggression. The first two mislead and the third replaces learning and negotiation with fear and obedience.

Left-wing political parties are intellectually vacuous and lack “animal spirits”–a problem captured by a US podcast recently asking, “Has anyone seen the Democrats?” Meanwhile, the UK Labour party of 2025 has mind-melded with the Conservative party of 2015: private equity will rebuild Britain for us; we’ll fix housing by breaking planning; first seek growth not green; we must build a third runway at Heathrow airport!

I’m an instinctive contrarian, and can rattle off counterforces for each of these. But how much force do any of them have right now?

This question is made more acute by the current weakness of collective energy and will. I have a certain faith in dialectical thinking, and have the sense that dominant trends will be countered and eventually elevated by their opposites into a higher synthesis. But when is “eventually”?

Various things are convincing me that “eventually” means the 2030s rather than the decade we’re enduring now.

First, tension and conflict are rising in the 2020s, not falling. Two examples are the withdrawal of banks from climate groups and the US retreat from a global tax regime. In 2015, I expected global climate cooperation based on that year’s Paris COP agreement would be in place by 2025. Now 2035 seems more likely, even optimistic.

Next, there’s the way that crisis doesn’t lead nations to negotiated reform but to war. Ukraine, Gaza, Sudan are not anomalies in a basically progressive green transition but suggest a trend of more frequent and possibly wider wars.

Most perplexing to me is the unchanging sameness of the political terms of order since the rise of Reagan and Thatcher in 1979-80. Why do these dumb arguments still work so well?

The 1980s had the potential to synthesise the strengths of the preceding periods, taking the state-led building of social and physical infrastructure that typified 1945-1965 and improving it with the social-movement insights of the next 15 years (1965-1980). The strong welfare state might have become racially egalitarian without massive backlash. Corporations might have moved systematically to offering equal pay to women, and the auto industry might have conceded that the consumer rights movement had created a regulatory floor that would allow them to spend more to make cleaner and safer cars. Mixed economies could have developed international protocols to end environmental dumping and debt-based exploitation of the Global South.

Some of this happened, but against the steadfast opposition of the political establishment. Thatcher, Reagan, et al. systematically set economic prosperity against social equality and environmental goals. They defined racial integration as the enemy of regular wage increases. They claimed environmentalism was the enemy of employment. They also pursued economic policies that damaged overall wages and employment, thus creating the bad economic results that they could then blame on Black poverty and “tree huggers”.

Here’s one image of the Reagan-Thatcher economic record in the U.S.

Figure 1: Graph by Economic Policy Institute (2024)

A similar pattern became entrenched in Britain after the Coalition and Conservative governments took power in 2010.

The opposition parties did a poor job of answering the false claim that the problem was demanding social minorities rather than bad neoliberal economics. By the mid-1980s, the periods of social development and of egalitarian protest were replaced by what the macrohistorian Neil Howe calls the “unravelling”. Reaganism and Thatcherism undid the prosperity infrastructure and the ensuing revolts of consciousness (feminism, gay liberation, civil rights, the anti-war movement and the counterculture). The best features of the first two periods were chopped away mainly by encouraging people to become sick of them and to see other people as getting more out of them than they are.

Economic turbulence disrupted people’s lives without offering useful new ideas. Programmes that worked—defined-benefit pensions, unions, tax-funded health services, public housing, free university tuition—got in the way of some groups’ advantage. These groups could unravel positive programmes because the larger narrative had associated the programmes with affects like anger and resentment that made it easy to blame them for layoffs and stagnant standards of living.

A key problem has long been these grinding, exhausting political affects. It’s not just that strong groups (fund managers, wealthy taxpayers) attack these functional institutions out of self-interest. The problem is also that the spirit of the majority isn’t strong enough to fight these powerful groups with the required level of intensity.

So the unthinkable in 1955 (charging market rates for public university tuition) became inevitable in 1985.The balance of power had shifted, of course, but beneath that, the balance of confidence had shifted. The right came to win most of its political battles not on the basis of superior facts, arguments or outcomes—whose quality was grossly overstated—but on the basis of a sense of destiny. They won the battle of confidence, which allowed them to win the battles of organisation and of action.

Much or most of the right’s confidence flows from its hatreds. It engages its followers in unending scapegoating—Reagan’s Black “welfare queens”, Bush’s terrorists, Trump’s criminal immigrants. It’s easier to play hard against an enemy, and the right excels at turning its opposition into an enemy to be despised.

Yet this abundance of right-wing contempt doesn’t explain why the left has so often adapted to its designated role as other, as outsider, as a marginalised player and not the popular force. Some have said the left is averse to holding power, but if so we should see that as symptom rather than disease. Is it rooted in shame at the knowledge of past defeats? Is it the fear of one’s total annihilation that shame replaces and eases, in Louise Braddock’s reading?

Annihilation is the threat the right continuously wields. It comes in the form of street violence in Germany and the UK. It comes in the form of witch-hunts and purges of the kind Trump and Musk are conducting in the US government, a hardcore revival of the anti-communist McCarthyism of the 1950s.

Annihilation is also the right’s own deepest fear. The hatred and the vicious fighting arises from a felt existential threat, however unjustified. “Jews will not replace us,” they chanted in Charlottesville in 2017. “English till I die,” they chanted in Southport in 2024. Right-wing politics stokes the shame of this unconscious fear of annihilation instead of addressing it. The power of Trump or Putin or Modi lies in making their followers feel worse rather than better.

I draw four lessons.

First, left politics has often been about feeling good rather than bad, and it must be this again.

Second, we have to confront shame-become-political-hate as a treatable syndrome, and not allow it to roll on as though it is either human nature or a legitimate expression of economic grievances.

Third, we must reconnect the economic and cultural issues that Reagan and Thatcher set against each other. Economic renewal, identity-based egalitarianism and epic climate policy should be shown to require and reinforce each other. We do not need to choose one over another; in fact, we must not.

The final lesson occurred to me, for some reason, in the memory of an exchange in the novelist Haruki Murakami’s masterpiece, The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle. One character has bequeathed to the narrator an abundance of new knowledge, and the narrator wonders what to do with it all. The knowledge-giver tells the narrator, “when the flow is up, go up. When the flow is down, go down”.

These days, the flow is down. Nothing good will happen on its own. No corrective forces of technology or nature will restore the balance. There is in fact no such thing as an energy transition. Nothing good will come to those who wait. “Going down” means full engagement in the already existing fight.

The left has been the target of a culture war for 50 years. The other three measures I’ve named can rebuild society to deal with climate change and the other headwinds. But they will never happen unless the left begins to fight, fight like it hasn’t fought in the Anglosphere for about a hundred years.

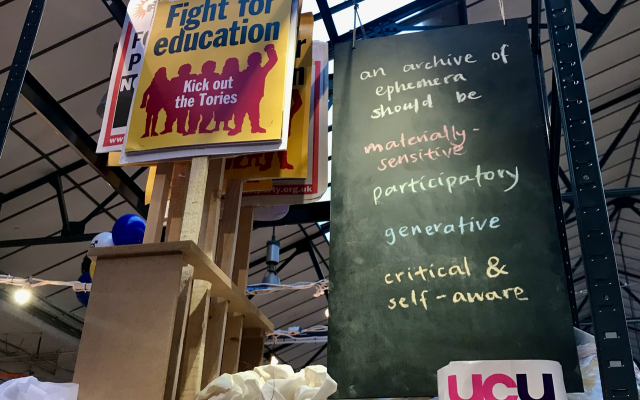

Feature image by Lucy Newby.

Bulletin posts represent the views of the author(s) and not those of the ISRF.

Unless stated otherwise, all posts are licensed under a CC BY-ND 4.0 license.