A New Regulatory Framework for University Cuts

Published on: July 3rd, 2025

Read time: 9 mins

I spent the second half of June on the road, speaking at conferences in London, Dublin and Berlin. A common theme was the stark contrast between quality and precarity—the high quality of the research in contrast with the academic staff firings and university programme cancellations I heard about day after day.

I’m an institutionalist. Institutions often sabotage human powers but also multiply them. They are as important as technology to collective capacity, and probably more so. Tech solutions never work correctly without being defined, steered and enabled by good social systems. And this is true for the research findings of the social sciences and humanities.

I’ve been studying and writing about research funding and infrastructure for many years. The humanities have been funded very badly and remain generally unconstructed as research disciplines. This isn’t to knock humanities scholars, but to compliment them – they’ve accomplished great things with few resources.

Amid pockets of infrastructure, such as the Consortium of Humanities Centers and Institutes which staged the meeting I attended in Berlin, the humanities have not developed the knowledge systems evolved by the science and engineering fields a century ago. Humanities research is often superb – today’s early-career work has never been better – but it lacks the scale, scope, speed, and visibility a modern infrastructure would allow.

Most humanities research takes place in universities. At the London conference, Stefan Collini spoke about his new magnum opus, Literature and Learning, which details how the study of English literature became a defining practice of British universities. How’s that going these days?

In London on a Saturday, I was told that the University of Exeter is introducing voluntary redundancies with a special focus on lower-enrolment humanities departments. Then, on Sunday, a friend emailed about the latest mass redundancy announcement at Goldsmiths College London, incredibly its fifth since 2010.

The following Wednesday, I heard more bad news. At a very good conference in Dun Laoghaire on Dublin Bay, appropriately called “Dis/trusting the Institution(s) of Literature,” I was told that a Russell Group university will be merging or closing its English department. That same day, a member of a second Russell Group university's English department gave a very good talk about the difficulties of departmental solidarity across years of cuts and strikes. And the following day, while sitting in the audience at another panel, the Bristol speaker got an email announcing their department would merge or close by 2027.

And on it went. On Friday, a doctoral student at another university said her advisor and a PhD committee member had been given layoff notices. While not long after, in Berlin, old friends told me the new rector of their German art school was making her mark by railroading the termination of their unique MA programme.

As the next conference started on Monday, so did new stories of cuts.

On the whole, many higher education managers are routinely making massive, savage cuts to education, to student learning, to doctoral research, to accumulated knowledge, to new knowledge, to institutional resources built over many years, to systematised intelligence, to the workforce, to knowledge workers, and to the social benefits of universities.

Lest this seem like an unlucky run of negative anecdotes, two researchers have published the results of a recent survey of UK academics called Universities Degraded. The survey focused on University and College Union (UCU) members at universities where managers were implementing redundancy processes or had done so in the past five years. They found general degradation. “91% [of respondents] noticed a deterioration in working conditions, including less collegiality and lower morale; 90% cited emerging anxiety, stress, depression or other health problems as a result of redundancy processes; 87% said workloads for remaining staff increased when colleagues were made redundant.”

At the root of all this, “73% of HEIs are failing to adequately consult with those individuals at risk of redundancy.” And the same percentage “of senior management teams are failing to implement/accept suggested alternatives to redundancies”.

There’s evidence that downsizing consultation protocols are very weak, and that at least half (54%) of managers are “bullying” staff into accepting redundancy packages.

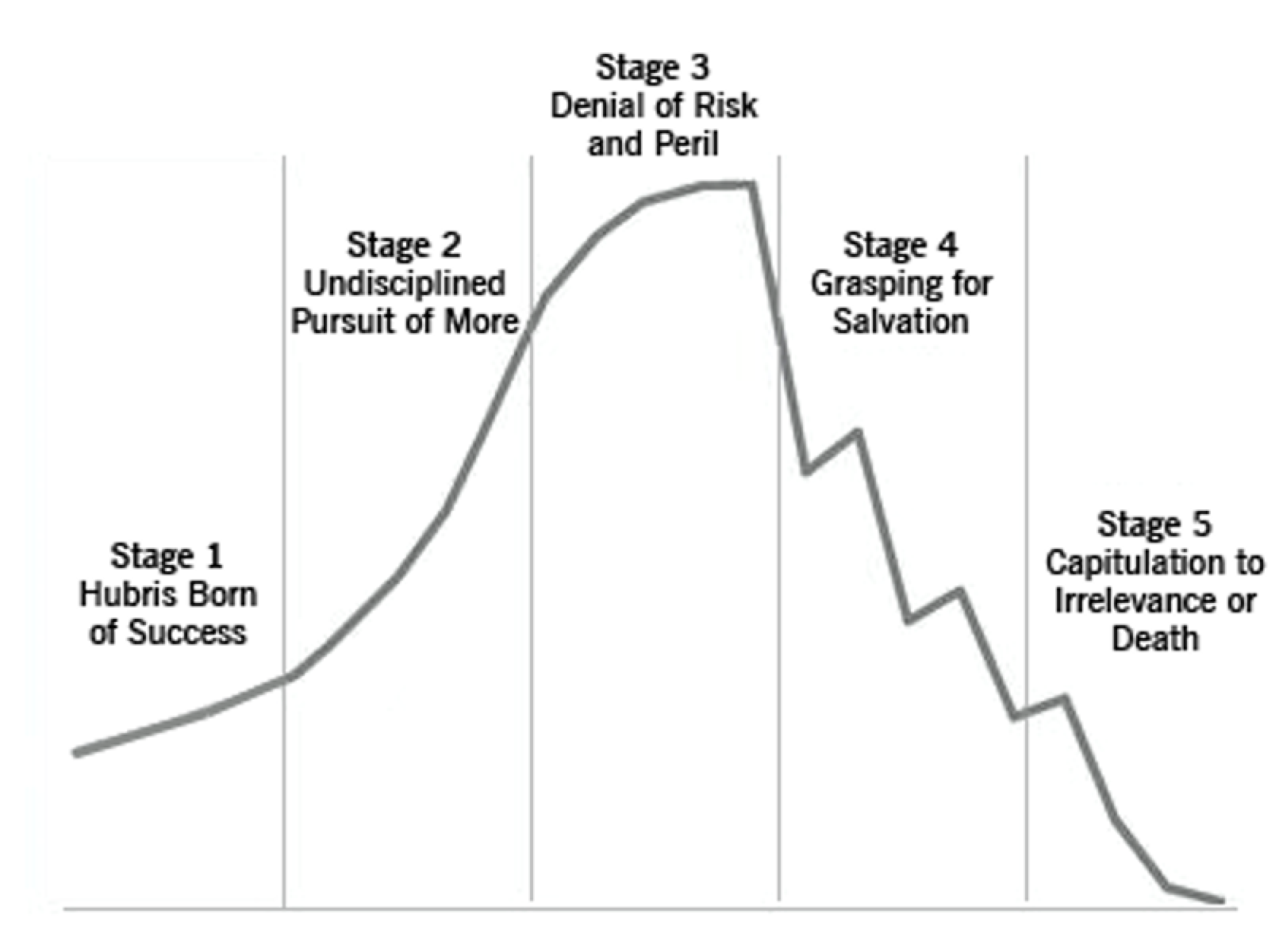

One image that sticks in my mind after years reading too much management theory is Jim Collins’ arc of doom from How the Mighty Fall (2009). The curve looks like this.

Jim Collins’ arc of doom from How the Mighty Fall (2009).

UK higher education went through at least two Stage 3s of denial: first, around 2015-17, when managers thought high fees had more than made up for the Tories’ cuts to central funding and to student grants and their universities "borrowed" for student accommodation and other growth projects; and second, during the Covid period, when costs dropped and international student enrolments rose.

Three years later, the sector is well into Stage 4: Grasping for Salvation. In this stage, measures like firing people and closing programmes always seem tough yet rejuvenating, yet always block recovery and hasten decline. Goldsmiths has already proved this on four separate occasions.

The final stages blend “grasping” and “capitulation” in a toxic and potentially fatal mix. The tales of cuts, closures, and intrusions I heard over the last month point to three main elements.

First, programmes and collective expertise that took decades to build are abruptly thrown away.

Second, financial factors dictate academic outcomes with unappealable force. Finance is owned and deployed by administrators with unilateral legal and institutional backing from governing bodies. Usually no coherent and complete financial data are offered such that staff can understand the forces destroying their careers, much less develop and negotiate a better plan.

Third are the partners in destruction: staff apathy, fatalism and/or resignation. These attitudes are both completely understandable and now completely unaffordable. They come from academics seeing no mechanism for engagement or authorized path to better results.

To repeat, it’s understandable that the relatively powerless feel defeated. But fatalism locks in the idea that firings, closures and cuts are the only solutions available to UK and US university managers. This idea is slowly ruining the intellectual functions and educational effects of higher education, perhaps irreversibly.

Studying for my next conference, our ISRF workshop, “New Social and Cultural Frameworks for ‘Artificial Intelligence,’” I read a report on frontier AI policy in California. The authors compare AI to some previous industries that in their early decades either repelled or controlled regulation: petrol refining that used lead, pesticides, tobacco, and oil companies.

In these cases, powerful industries falsified the results of their internal research and wrongly claimed safety where none existed. The most destructive example is the fossil fuel industry. One industry body published a definitive report on its products creating atmospheric heating—in 1968. They suppressed it and deliberately deceived and confused the public for decades afterwards. Here we are, with a seriously damaged climate and many politicians still in denial.

Universities are not tobacco or oil companies. But their managements have long concealed or distorted the effects of their marketised business model, with a dependence on student debt paired with inadequate public funding.

At the same time, the managers with financial authority are as unregulated as were pesticide manufacturers and oil companies—and as unaccountable to staff, students, research, teaching, knowledge, public benefit or society. Pro forma consultations with unions focus on completing redundancies rather than collaborative rebuilding.

The result is the long-term decline of an essential social sector at the core of so-called knowledge societies, future industries, basic productivity growth, and stronger, happier societies with better intellectual lives, that has entered long term decline. Yet I see no urgency in government, in management, or even in much of the sector. I see plenty of resignation.

One conclusion is that universities need a regulatory framework as badly as AI, chemical and fossil fuel companies do. The obvious model is an Environmental Impact Assessment or Statement. It would function as an Educational Impact Statement (EIS).

This university EIS would require managers to assess systematically the educational effects of proposed financial change. They would need to make a full assessment of the problem they are trying to solve, evidenced by complete financial data. It would specify the institution’s overall financial need and state relevant constraints like the covenants on bank loans that are now generally confidential.

After defining the action in its particulars, the EIS would project in detail the proposed actions’ effects. This is essential for the environment – and also for the knowledge ecosystem. What are the opportunity cost calculations driving the restructuring? What are the estimated returns on investment for different alternatives? What are the anticipated losses to teaching (losses within offers), to research (loss of knowledge, loss of future capacity) to the workforce, to the public (reductions in service to local, regional, and international needs). For Goldsmiths 5th downsizing, this would include detail on the harms the cuts do to the creative industries’ knowledge base.

The EIS would identify alternatives to programme reduction or closure: there are always several if not a half-dozen worth considering. It would spell out why these alternatives are inadequate, in enough detail either to convince sceptics or allow the institution to switch to a less-destructive plan.

The EIS would get a full public airing through a multi-step, scheduled process, with staff and community comment. Outcomes would be debated and negotiated rather than imposed.

This is the barest outline of an EIS process for universities. It is not utopian, but adapts a process that is well-established in other sectors. It is intelligent and minimally respectful of people’s careers and labour and of their institutional achievements created over years.

It would take time and much fussing to structure correctly. But two things I am sure of.

It would be relatively democratic rather than autocratic, where autocracy is a standing embarrassment to the moral authority of universities.

And it would produce better alternatives for both solvency and education than what universities are producing now.

Feature image by cottonbro studio via Pexels.

Bulletin posts represent the views of the author(s) and not those of the ISRF. Unless stated otherwise, all posts are licensed under a CC BY-ND 4.0 license.