In this contribution to Bulletin 29, Sieglinde Lemke critically explores how education needs to change if we are to build sustainable ways of acting, thinking, and being.

Sieglinde Lemke

Image via Unsplash.

What are the necessary competences the next generation should obtain that would make for a more sustainable future? Possible answers to this simple question include: we need education for sustainability, environmental education, and education for sustainable development (ESD). While these concepts are used interchangeably, some scholars avoid the later term to set themselves off from the growth-oriented ideology of sustainable development. But even UNESCO’s ESD Roadmap for 2030 foresees a development that combines teaching the relevant scientific facts with the basics for ecological living. Its declared mission is to raise awareness towards climate destruction and ecocide, but also towards gender equality, global citizenship, and cultural diversity. It sets out to teach students how to preserve natural resources, how to interact with their environment in non-violent ways, and much more.[1] The ESD roadmap introduces teachers and students to the broader “culture of sustainability,” its social values, ideals, norms, and practices. Such an inclusive approach aligns with the Sustainability Development Goal (SDG) 4, an equitable quality education. Moreover, this culture of sustainability encompasses a new, decidedly sustainable, worldview that will allow the future generation to upend the non-sustainable lifestyle of past generations, thereby diverging from technocratic solutions for sustainability. The UN has explicitly, and repeatedly, emphasized the importance of cultural factors for sustainable development.[2] And several Sustainability Development Goals (e.g., SDG goals 3, 11, 12, 16, 17) center on cultural skills while others (e.g. 1, 2, 6, 8, 9, 13, 14, 15) are more specifically geared towards the economy and the natural environment to secure e.g. access to clean water or to put an end to hunger and poverty.

This very interdependency between cultural factors and sustainability is the focus of Janet Stephenson’s monograph The Cultures Framework, which conceptualizes sustainability outcomes through a triad of 1) motivators: i.e., norms, ideas, knowledge; 2) activities: i.e., routines and rituals; 3) materiality: i.e., physical and digital objects, products and acquisitions.[3] To Stephenson, we need to closely consider the “culture ensemble” to better understand, and teach, sustainable ways of thinking, acting, and what one might call ‘having.’[4] If we ignore this culture ensemble, neither the present nor the next generation will be able to effectively move towards a more sustainable future.

Calls for a cultural approach to sustainability have been around for decades. They come by different labels including those of ecopedagogy and ecoliteracy, emphasizing the role of socio-psychological factors.[5] Isabel Rimanoczy’s ecoliterate approach, which I elaborate on below, is notable in this regard since it provides guidelines on how to attain, and teach, “the sustainability mindset.”[6] Before I expound on these socio-psychological factors, let’s consider two other common denominators that academics, activists, and policy-oriented initiatives seem to agree on since they insist that sustainability education has to be holistic and transformative.

Rhetorical appeals to a “holistic” education are omnipresent. Mostly ‘holistic’ is used synonymously with transdisciplinary to assure that the many facets and interconnections of (non-)sustainability are taken into account. To adequately assess human-nature and human-planetary relations, we quintessentially need both the social and the natural sciences. This inevitably transdisciplinary approach makes ESD ‘transformative’ in the sense that it trans- or re-forms hegemonic (non-sustainable) practices by bridging disciplinary divisions. Indeed, sustainability education integrates knowledge from many different fields, ranging from ethics to engineering, from cultural to digital studies, from cognitive psychology to molecular biology.

Moreover, ‘holistic’ also refers to the multiple skills it takes to transform our current lifestyle in order to practice new, more sustainable ways of thinking, acting, having, and being. Since sustainability, like the disregard for sustainability, manifests on a personal and a collective level, locally and globally, in public and in private, in our everyday lives and our civic, legal, and political cultures, it is pervasive and all-encompassing. Lastly, holistic (sometimes) refers to an approach that acknowledges diversity, equity, and inclusion. In that sense, ESD overlaps with DEI.

A more holistic (higher) educational system is not utopian. Recently, the pan-European initiative Sustainability Education for Europe (SEFE) demanded that integrated versions of ESD become a part of students’ basic formal education.[7] Accordingly, sustainability education will have to become omnipresent in the educational system. To face up to challenges surrounding climate change, biodiversity, and environmental justice, ESD trains students to upend fossil-fuel lifestyles. This means that received habits of thinking, acting, having, and being will have to change. But this in turn demands a sweeping reform of university and high school curricula so that sustainability-relevant topics are taught across the board in various faculties. Instead of being limited to designated degree-granting programs, sustainability issues will become a running theme in various subjects and classes. Students will learn, for example, to calculate energy consumption in mathematics, analyze climate fiction in language and literature classes, and examine eco-interloops in biology classes.[8] To systemically integrate ESD curricula into universities worldwide, it is vital to have a good grasp of the scholarly discourse surrounding sustainability as well as sustainability education.

When the term ‘sustainability’ was first introduced in 1969, it did not refer to education but to the protection of natural resources.[9] But as early as the 1980s, scholars came to advocate for the institutionalization of ecological learning within the framework of public education. The editors of Ecopedagogy (1984), Gerhard de Haan and Wolfgang Beer, pursued a radical approach that exceeded “environmental education.” In their view, ecological disasters were “a result of industrial production and lifestyle excesses [caused by] fundamental patterns of thought and action within our society (i.e., culture).”[10] In other words, capitalist production and consumption leads to environmental destruction. Ecopedagogy, thus understood, tries to abolish this pernicious system. Accordingly, ecopedagogy, they insist, “always aims for transformation.”[11] Plus, the editors and contributors to Ecopadagogy were convinced that “the domination of nature always goes hand in hand with the domination and exploitation of people.”[12] Hence, their understanding of ecopedagogy overlaps with contemporary definitions of sustainability since both seek environmental as well as social justice. When Haan and Beer argue that we can only overcome this exploitative attitude at the root of ecological destruction if our educational system assumes more “integrative synthetic perspectives,” they anticipated calls for a holistic approach to ESD.[13]

Apparently, the term ‘education for sustainable development’ was coined in 1992 at an international conference in New Zealand by Stephen Sterling, then professor at Plymouth University. In the 2000s and 2010s, Sterling started replacing the term with ‘education for sustainability’ to avoid the growth-oriented notion of ‘development.’ In the 2020s Greg William Misiaszek, who has published widely on ecopedagogy, also rejected the label ESD, arguing that environmental and social violence are always interrelated.[14] This radical undertone seems to be missing in the policy-oriented discourse that prefers the term ESD. Those who use the label ‘education for sustainability,’ ‘sustainability education,’ and ‘ecoliteracy’ usually set themselves off from mechanistic, managerial, tech-, and growth-driven approaches to ‘sustainable development.’[15] Most scholars who try to implement ‘ecopedagogy’ in public education aim at transforming the educational system to secure that new ways of teaching and thinking enhance sustainability outcomes. The follow-up question then must be: how can we manage to do so? What does it take to design holistic, transformative curricula?

Firstly, it takes systems thinking to examine natural food cycles, for example. Students have to understand how e.g. planting, growing, and harvesting are impacted by climate change; how composting and recycling depend on alternative farming methods; and how carbon reduction relies on renewable energy sources. It takes systems thinking to grasp how organisms—from bees to bugs, from cows to fungi—are interconnected. Likewise, we have to acknowledge that consumers, politicians, entrepreneurs, and academics all play their part in this collective ensemble that pushes for sustainable outcomes. Hence, we need to see into nature’s and humans’ connectedness.[16] Secondly, it takes a more humanistic value system. As early as 2001, Sterling advocated for cultural change aspiring to implement both humanistic and ecological values in his book Sustainability Education: Re-visioning Learning and Change.[17] Thirdly, as mentioned above, these approaches embrace a transdisciplinary, holistic approach to sustainability. Lastly, all these approaches—be they called ecopedagogy, education for sustainability, sustainability education, ecoliteracy or sustainable literacy—are imbued with a strong sense of idealism.

‘Ecoliteracy’ offers perhaps the most comprehensive agenda since it gravitates around the mental, psychological, and cultural capabilities the current generation should exercise so that the next generation might live sustainably. It is not just about teaching ecologically relevant facts such as CO2 emissions, ozone depletion, reforestation, or permaculture. Anecologically literate person is someone who does not just understand the basic principles of ecology but who also embodies them in their daily life, Fritjof Capra insisted as early as 1999 in his groundbreaking book Ecoliteracy: The Challenge for Education in the Next Century.[18] Capra’s idea of ecoliteracy overlaps with Sterling’s notion of sustainable education as it centers around both acting and living sustainably. Both validate alternative ways of knowing, thinking, and being. Ecoliteracy also overlaps with received understandings of environmentalism as it is concerned with the relationship humans have with their surroundings. Moreover, it sometimes overlaps with ecocriticism using literary or visual texts to instruct students to become ecoliterate. Yet, ecocinema and ecofiction are not necessarily subject matters in ecoliteracy.[19]

Sustainability literacy, as Arran Stibbe defines the term in his eponymic handbook, is synonymous with ecoliteracy. As the handbook’s subtitle, “skills for a changing world,” suggests, Stibbe’s volume covers a wide range of activities and capabilities.[20] The contributors to this transdisciplinary volume address for example the need for waste reduction as well as for self-care, to them, training one’s emotional wellbeing is just as important as advertisement awareness. Sustainability Literacy openly questions the consumerist capitalist paradigm by arguing that capitalism’s obsession with perpetual growth has brought us to the brink of ecological collapse. They claim that advertisement spurs the inexorable desire for consumer objects and pushes mass production, which can deplete natural resources, yield toxicity and/or increase carbon dioxide. To become sustainability literate, students need to rigorously question and critique neoliberal consumer culture.

In fact, many contributors to the handbook, such as Ling Feng and Stephen Sterling,[21] tackle the destructive effects of the dominant ideology of Western societies and specifically individualism’s disposition of self-centeredness. Aspiring to be better than others, the “‘hyper-individualistic self’ loses the capability for relationships with nature and with people.”[22] Pro-social skills diminish with highly competitive people who primarily think about themselves and not relationally, which is also detrimental to the environment. “If we want the chance of a sustainable future, Sterling maintains, “we need to think relationally. That’s it, full stop.”[23] Accordingly, sustainable literacy aims at introducing students to “the commons way of thinking.”[24] This relational or commons way of approaching the world resonates with the emergent research field that focuses on human-nature connections. Defining sustainability, as “a method to improve our relationship to resource,” Wise et al. scrutinize “nature-connectedness” and ways to reconnect by forming habits of reciprocity and nature connection through five pathways: senses, emotions, meaning, beauty, and compassion.[25]

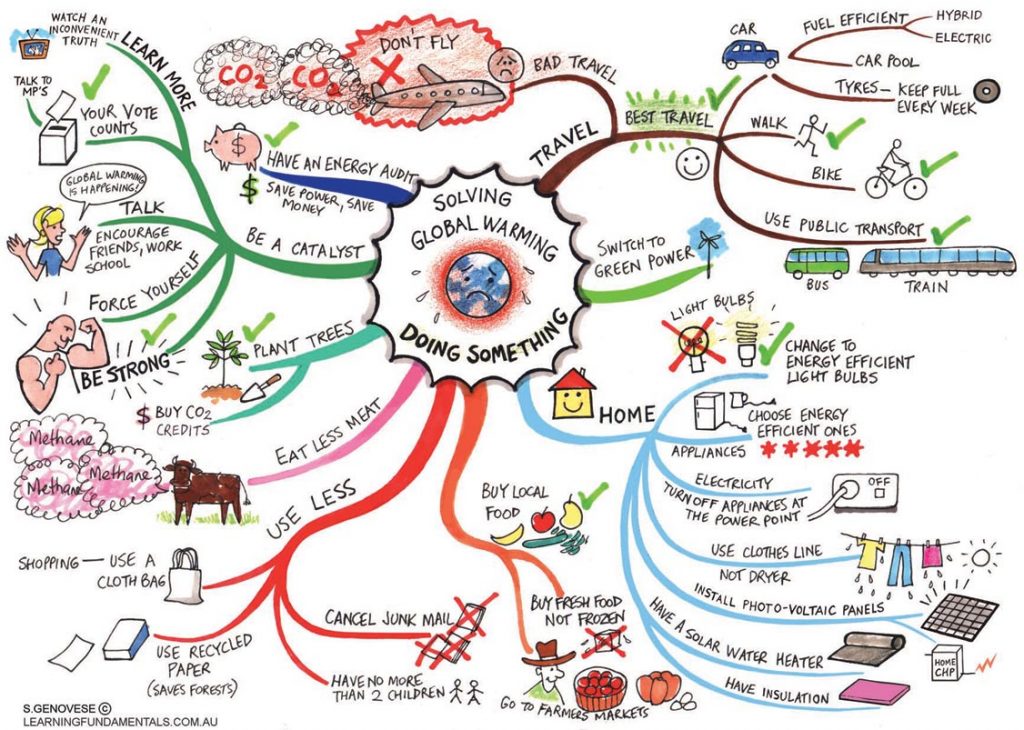

Of course, we cannot reduce the climate crisis or ecocide to a relationship problem. But any attempt to solve the climate crisis takes accurate scientific knowledge, a systems thinking approach, as well as a relational approach. To protect the environment and meet the SDGs, it certainly takes corporate and governmental responsibility, but any attempt towards social change has to go hand in hand with training sustainability or eco-literacy. To come back to the above-mentioned triad—acting, doing, and being—students could be asked to reflect on their life style choices such as eating (less) meat, buying local food, saving energy at home, flying (less), and recycling.[26] One exercise could be to critically examine this mind map on how to combat global warming.[27]

But doing or acting is not only about the obvious sustainable choices. It necessitates different ways of thinking.Doing—i.e., combatting environmental destruction—involves system thinking. In contrast to traditional thinking, systems thinking does not operate with oppositions and dualism. It considers the network of mutually influencing relationships to assess how various components interact forming an integrated whole. This approach depends on transdisciplinary collaborations to also acknowledge the interconnections among various disciplines. While traditional thinking chooses an analytic approach to determine causal relations, systems thinking looks at the bigger picture. Yet, systems thinking is not necessarily the same as Sterling’s relational thinking.

What are sustainable ways of being and how to teach them? Isabel Rimanoczy’s skill-based approach to build a sustainable mindset is instructive in this regard.[28] Out of the 12 principles laid out in her book, I want to introduce seven principles, all of which center on the cultural aspects of sustainability education. The first principle is “ecoliteracy,” which teaches students not only about the ecosystem and its interconnections (e.g., the impact of rainforest destruction on the release of captured CO2), it also seeks to foster students’ emotional intelligence and creativity. It aims to equip them with strategies for overcoming self-limiting thoughts and strengthening their intuition. The underlying assumption is that students will only be able to reflect on their mindset and transform it, if they are emotionally stable. Only if they feel somewhat confident, will they reflect on ways to reduce their carbon footprint or other measures to protect the planet—i.e., Rimanoczy’s second principle “My contribution.” Since many students experience climate anxiety, they have to learn to resist the tendency of giving in to climate pessimism, which usually leads to inaction.

Figure 2: The Four Content Areas of the 12 Sustainability Mindset Principles. Image by Isabel Rimanoczy.[29]

The principle “long term thinking,” Rimanoczy links to the “Seventh Generation Principle,” first documented at the Iroquois Confederacy (between 1142 and 1500 AD) and their commitment to base any decision-making process on the consideration of whether it can secure sustainable conditions for at least seven generations into the future. In addition to longevity, the “both+ and thinking principle” teaches students to go beyond either/or, dualistic, linear perspectives. To transcend the linear mindset that has driven the economic growth model of profit-seeking agro-industrialization, “both+ and thinking” skills enable students to integrate dualities, challenge hierarchical domination models and accept paradoxes. Principle no. 6, “interconnectedness,” manifests in nature’s web of organisms but also in the interdependence of humans.[30]

Indigenous cultures across the globe are well aware that humans, animals, and all of nature are connected, but Rimanoczy points out that most spiritual teachings including Buddhism and Taoism presuppose that all beings are interconnected. She defines “a spiritual person [a]s someone who reaches beyond his or her self … and assumes responsibility for caring about others.”[31] In that sense, the spiritual aspect of being intersects with personal or corporate attempts to enhance our well-being. Principle no. 12 “mindfulness” is key, Rimanoczy suggests, because “being fully present, experiencing connectedness with all that is, enhances awareness and compassion which predisposes to social and environmental actions.”[32] In other words, the sustainability mindset model trains ways of being, thinking, and acting that fundamentally challenge the hegemonic non-caring, hyper-individualistic ways.

To conclude, a common denominator of the above discussed pedagogical approaches to sustainability is that relationship skills and a close connection to nature are quintessential. Therefore teachers and students alike must learn how to sustain their own physical and mental well-being to advocate for the well-being of all humans, non-humans, the climate and the planet. To foster a culture of sustainable development, we have to acknowledge the basic fact of our connectedness as humans (with nature and other humans), practice systems thinking and transdisciplinarity. We need to not just produce solar panels or sign climate treaties but also educate students to question the value system of the Anthropocene.[33] All these pedagogical endeavors, explicitly or implicitly, push towards the Symbiocene promoting a value system based on interconnectedness and stewardship that reintegrates humans and the rest of nature. For that to happen, students and teachers need to learn to become more empathetic, caring, and mindful. For humans to cultivate a mindset that yields sustainable outcomes, we need to learn to act, think, and, essentially, be (i.e. have and live) so that future generations won’t suffer from perpetual heatwaves or flooding. In this holistic education for sustainability, academic disciplines such as Cultural Studies, Psychology, and Sociology (will) play a pivotal role.

Students in Sociology or Cultural Studies—including its many sub-disciplines such as Ethnic, Queer, Digital, Film, Game, Women’s Studies—have, for decades, been trained in critical media literacy skills, DEI, intersectionality, social and gender inequality. Most students in those disciplines are already aware that advertisement strategies boost mass consumption thereby bolstering the hegemonic culture of environmental degradation. They know that a culture of hyper-individualism and self-branding can harm the wellbeing of the many. Adding to this knowledge base comes the training of critical ecoliterate skills that allows students to question the Anthropocene and prepares them for the Symbiocene. But only a holistic mindset that integrates environmental, social, and psychological proficiency will get us there.

Let me end on an as-if scenario: Even if we were to achieve current climate goals and stop global warming in, let’s say, the next six years, heat waves, floods, droughts, and air pollution would have lasting effects. While renewable technologies are quintessential, technological development alone is not enough to secure a sustainable future. Laws that protect the environment and ensure human rights are needed. Also the recently introduced EU laws mandating companies, multi-national corporations and financial institutions to disclose ESG information are certainly helpful. Yet, in the long run we as a species—and particularly the consumers in the Global North since we are mostly responsible for the environmental destruction—have to develop a holistic culture of sustainability. Schools and universities play a vital role in disseminating a value system that substantially transforms the received, ego- and anthropocentric, world view. A thorough reform of education plans, curricula, and teacher trainings will be instructive in spreading the seed for sustainable ways of acting, thinking and being. Who knows, maybe, seven generations down the line we will have become more ecoliterate.

Footnotes

[1] These, and more, learning targets comply with the roadmap on ESD the UN published recently. Their goal is to “ensure that all learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development, including, among others, through education for sustainable development and sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality, promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development” (14). This list of skills and targets should be ensured, according to this plan, “by 2030” (14). While it is unlikely that this idealist vision will be realized within this decade, this very ambitious list does include many essential pillars for an education that aspires towards making the future more sustainable. UNESCO, “Education for Sustainable Development: A Roadmap,” UNESCO Digital Library, DOI: 10.54675/YFRE1448.

[2] See United Nations, “Culture and Sustainable Development,” 21 May 2019, accessible at: https://www.un.org/pga/73/event/culture-and-sustainable-development/; and UNESCO, Culture: A Driver and an Enabler of Sustainable Development, May 2012, accessible at: https://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/pdf/Think%20Pieces/2_culture.pdf.

[3] Janet Stephenson, Culture and Sustainability: Exploring Stability and Transformation with the Cultures Framework (Cham 2023: Springer), chapter 4. Stephenson is the Director of the Centre for Sustainability at the University of Otago, New Zealand. She heads an international, multidisciplinary research team on energy cultures.

[4] In her Inaugural Professorial Lecture titled “Culture and Sustainability”, broadcasted on 16 Sept. 2021, Stephenson uses the triad of practices, norms, and materiality, which respectively corresponds to doing, thinking and having. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AJJiN84BRGc.

[5] I sketch the evolution of cultural approaches to sustainability from the 1980s onwards (in this article further below), yet, for an early explicit reference I recommend the article ‘Three Steps Towards a Culture of Sustainability,’ published more than a decade ago in Sustainable Development: Culture, Knowledge, Ethics, edited by O. Parodi, I. Ayestaran & G. Banse (Karlsruhe 2011: KIT Scientific Publishing): 75–92.Parodi also explored personal factors adding to the emerging field of personal sustainability science. See also Pascal Frank, Johannes Wagemann, Julius Grund & Oliver Parodi, ‘Directing personal sustainability science toward subjective experience: conceptual, methodological, and normative cornerstones for a first-person inquiry into inner worlds’, Sustainability Science 19 (2024): 555–574. Another pioneering article was Davide Brocchi‘s “Der kulturelle Ansatz der Nachhaltigkeit,” published in 2006.

[6] Isabel Rimanoczy, The Sustainability Mindset Principles: A Guide to Develop a Mindset for a Better World. (Abingdon 2021: Routledge).

[7] See https://www.sustainabilityeducation.eu. The European Sustainability Competence Framework lists 12 necessary skills relevant for curricula design: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC128040

[8] For more details on curricula reforms, see the publications of different relevant national platforms: e.g., in France, the École ou Établissement en Démarche globale de Développement Durable (E3D) provides ample teaching material and curricula just as the German initiative of ESD, Bildung für Nachhaltige Entwicklung (BNE) offers not only online material but also published Jörg-Robert Schreiber & Hannes Siege (eds.),Curriculum Framework: Education for Sustainable Development (2016: Cornelsen).

[9] In 1969, the U.S. National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) defined sustainability as “the ability to maintain or improve standards of living without damaging or depleting natural resources for present and future generations.”

[10] Gerhard de Haan & Wolfgang Beer, Ökopädagogik: Aufstehen gegen den Untergang der Natur (Beltz 1984: Die blaue Reihe), 9, author’s translation.

[11] Ibid., 135.

[12] Ibid., 136. The original German read: “Naturbeherrschung geht immer mit Menschenbeherrschung einher.”

[13] Ibid.

[14] Greg William Misiaszek, Ecopedagogy: Critical Environmental Teaching for Planetary Justice and Global Sustainable Development (London 2020: Bloomsbury).

[15] Greg William Misiaszek even capitalizes the D in esD to distinguish it from esd. See Greg William Misiaszek, ‘Ecopedagogy: Teaching Critical Literacies of “Development”, “Sustainability”, and “Sustain-able Development”’, Teaching in Higher Education 25, no. 5 (2020): 615–632.

[16] See the volume by that title, which brings together scholars from many fields and urges for a radical transformation of our value system: Gerald Hüther & Christa Spannbauer (eds.), Connectedness: Warum wir ein neues Weltbild brauchen (Bern 2012: Huber).

[17] Stephen Sterling, Sustainable Education: Re-Visioning Learning and Change (Totnes 2001: Green Books).

[18] Whereas ‘ecological literacy’ is about understanding the principles of organization that ecosystems have developed to sustain the web of life, Capra suggests that ‘ecoliteracy’ offers an ecological framework for educational reform. His pioneering view on ecoliteracy, which emphasizes ecological over educational matters, differs from Daniel Goleman’s approach since his 2012 publication Ecoliterate: How Educators Are Cultivating Emotional, Social, and Ecological Intelligence focuses on the necessary mental skills.

[19] A case in point is the activist website https://www.ecoliteracy.org, which offers teaching material that focuses on, e.g., food, farming, and indigenous perspectives. Only rarely do they discuss artistic depictions or films. One exception is the documentary film Gather: The Fight to Revitalize Indigenous Foodways, accessible at: https://www.ecoliteracy.org/sites/default/files/media/ecoliteracy_gather_viewing_guide.pdf.

[20] Arran Stibbe (ed.), The Handbook of Sustainability Literacy: Skills for a Changing World (Totnes 2009: Green Books), 61.

[21] Ling Feng, “Ecological Intelligence: Viewing the Word Relationally,” in: A. Stibbe (ed.), The Handbook of Sustainability Literacy: 58–63; Stephen Sterling, “Effortless Action: The Ability to Fulfil Human Needs Effortlessly Through Working with Nature,” in: A. Stibbe (ed.), The Handbook of Sustainability Literacy: 77–83.

[22] Feng, “Ecological Intelligence,” 61.

[23] Sterling, “Effortless Action,” 77.

[24] The commons way of thinking, or the commons approach, assumes that “a) we live in a common life-world upon which we all depend; b) that any problem stems from a breakdown in relationships, and c) that solutions are primarily about restoring these relationships.” Justin Kenrick, “Commons Thinking: The Ability to Envisage and Enable a Viable Future through Connected Action,” in: A. Stibbe, (ed.), The Handbook of Sustainability Literacy: 51–57, 52.

[25] See Maggie Wise, Bruce Martin, Andrew Szolosi & Tamarine Foreman, “Habits of Connection: From Sustainability and Saviorship to Reciprocity and Relationship.” Journal of Experiential Education 46, no. 2 (2023): 238–255, 239, 245.

[26] One input could be to discuss ways to save carbon dioxide using a list the EcoClimate Foundation put together: “If every U.S. family replaced one regular light bulb with a compact fluorescent light CFL, it would eliminate 90 billion pounds of greenhouse gases, the same as taking 7.5 million cars off the road. If you reduce your household garbage by 10 percent, you can save 1,200 pounds of carbon dioxide annually. If you plant a single tree it will absorb approximately one ton of carbon dioxide during its lifetime.” See https://ecoclimatefoundation.org/top-10-things-you-can-do-to-reduce-global-warming/.

[27] Jane Genovese, “Combating Global Warming Mind Map,” accessible at: https://learningfundamentals.com.au/resources/combating-global-warming-mind-map/.

[28] Isabel Rimanoczy, The Sustainability Mindset Principles: A Guide to Developing a Mindset for a Better World (Abingdon 2021: Routledge). For more information about Rimanoczy’s multidisciplinary academic background (she holds a BA degree in psychology, an MBA, and a doctorate from Columbia University’s Teachers College) and ongoing activist endeavour of supporting educators worldwide, see https://www.isabelrimanoczy.net.

[29] Reproduced from Beate Klingenberg & Isabel Rimanoczy, “The Sustainability Mindset Indicator”, paper presented at the Eighteenth International Conference on Environmental, Cultural, Economic & Social Sustainability, University of Granada Spain, 26-28 January, 2022, accessible at: https://smindicator.com/conference-presentation-on-sustainability/.

212.

[30] While this notion overlaps with the above mentioned “relational thinking” and “commons thinking,” its emphasis on emotional skills and human interconnectedness adds a spiritual component to the culture of sustainability.

[31] L.M. English, as quoted in ibid., 162.

[32] Ibid., 194. Rimanoczy cites Frederick C. Tsao & Chris Laszlo, Quantum Leadership: New Consciousness in Business (Stanford, CA 2019: Stanford University Press).

[33] See Peter Sutoris’s Educating for the Anthropocene: Schooling and Activism in the Face of Slow Violence (Cambridge, MA 2022: MIT Press), which thoroughly explores the mental world of the Anthropocene. As an educator and environmental anthropologist, Sutoris launched his ethnographic project in India and South-Africa. He encouraged the students to produce self-directed films, allowing them to express their experiences of environmental degradation through representations of their communities.

Biography

Sieglinde Lemke is the author of Poverty, Inequality, and Precarity in Contemporary American Culture (Palgrave McMillan, 2017), Vernacular Matters in American Literature (Palgrave, 2009) and Primitivist Modernism: Black Culture and the Origins of Transatlantic Modernism (Oxford UP, 1998). She is also the co-editor of the volume Class Divisions in Serial Television (Palgrave, 2017).