In this contribution to Bulletin 29, Jane Hindley explores the potential of radical pedagogies to challenge and move beyond the limits of the dominant sustainable development framework.

Jane Hindley

Image via Unsplash.

Education either functions as an instrument which is used to facilitate the integration of the younger generation into the logic of the present system and bring about conformity to it, or it becomes the practice of freedom, the means by which men and women deal critically and creatively with their reality and discover how to participate in the transformation of their world.

Richard Schaull, 1972[2]

[The Sustainable Development G]oals are not only a missed opportunity, they are actively dangerous: they lock in the global development agenda for the next 15 years around a failing economic model that requires urgent and deep structural changes, and they kick the hard challenge of real transformation down the road for the next generation to deal with – by which time it may be too late.

Jason Hickel, 2015[3]

We found few new policies, institutions or budget allocations designed to further specific goals. Did any government change its laws to achieve the many intersecting transformations envisioned by the SDGs? Did any ministry in those governments create new programmes for implementing the SDGs? If so, there is little evidence of it. What we found instead are changes in discourse. Those in power now refer to the SDGs often. Yet the way they govern has not changed.

Frank Biermann, 2022[4]

Introduction

In July 2023, the UN announced that the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were failing and called on states to step up efforts to ensure that they would be achieved by 2030.[5] Two months later, the failure of the SDGs was corroborated by the findings of an independent evaluation published in Nature.[6] The fact that few states are on track to achieve the SDGs is no surprise given the grim dominance of neoliberalism, which continues to generate poverty, inequality and environmental damage. As Hickel wrote at the time of their launch, the SDGs were a substitute for genuine reforms and a transition to a new political economic model that will tackle the climate emergency.[7] Moreover, even in 2015 the SDGs were widely criticised, not only by radicals like Hickel, but also by experts and non-governmental actors as diverse as The Economist and the Gates Foundation. The weakness of the SDGs as tools for tackling the realities of the climate, ecological and social crisis not only reinforces the urgency of the “deep structural changes” that Hickel calls for. It also calls into question the central position these goals have recently come to occupy in mainstream approaches to climate and sustainability in higher education. As Biermann found in his systematic review,[8] SDG talk has proliferated across all sectors—and universities are no exception.

This short article starts by briefly critiquing the centrality of the SDGs in UNESCO’s most recent approach to climate and sustainability education. I focus on their 2020 report, Education for Sustainable Development: A Roadmap(ESD 2030), which has been influential in shaping national higher education frameworks and university teaching.[9] After highlighting the problems of ESD 2030, I then move on to discuss an alternative approach I developed ten years ago and have used ever since. This approach draws on my background in comparative political sociology, and early career research on social movements and regime transitions. However, as I explain, it was specifically inspired by the work of Paolo Freire, the Centre for Alternative Technology, and Naomi Klein. In the final section, I give examples of how I have used this approach to structure modules, short courses and public talks. Obviously, this is one of many ways to approach Education for Sustainability (EfS); but it may be useful to colleagues who wish to move beyond the contradictions and constraints evident in approaches founded on “sustainable development”.

1. The SDGS and UNESCO’s Approach to Education for Sustainable Development (ESD)

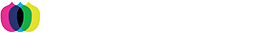

Figure 1: The UN Sustainable Development Goals & ESD Competences

Since the early 2000s when they launched the UN Decade for Education for Sustainable Development (2005-14), UNESCO has undoubtedly played a vital role in raising the profile of sustainability education. Their successive reports, guidance, and resources have generated debate and encouraged new norms around integrating climate and sustainability into national education policies, teacher training, and the ethos, operations and curricula of schools and universities. Until 2020, UNESCO’s ESD approach can be summed up as combining two main features. The first was a conception of sustainable development founded on the supposedly complementary “three pillars”, the economic, environmental and social. This conception dates back to the 1987 Bruntland report and has become a standard feature of sustainability textbooks. The second feature draws on a more radical educational tradition that ultimately dates back to John Dewey and is exemplified by the EfS approach advocated by Stephen Stirling.[10] This is the emphasis on active, dialogic, and experiential pedagogies aimed at enhancing students’ ESD competences (see figure 1) and capacity to become sustainable development advocates.

UNESCO’s 2020 report Education for Sustainable Development: A Roadmap (ESD 2030) maintains the emphasis on active pedagogies and competences. But it marks a shift away from the three-pillar conception and a wholesale adoption of the SDGs as core content and framework for ESD teaching. The report claims with almost missionary zeal that ESD can become an enabler for achieving the SDGs because it “raises awareness of the 17 goals”, promotes “critical and contextualized understanding of the SDGs”, and “mobilizes action towards [their] achievement”.[11] This report has been highly influential. In the UK, for example, following its publication, the SDGs were incorporated into the higher education Quality Assurance Agency’s 2021 Education for Sustainable Development Guidance, and they are also promoted by Students Organising for Sustainability, an offshoot of the National Union of Students. Additionally, the SDGs are increasingly used in universities as metrics for measuring institutional progress in integrating climate and sustainability education, as well as a framework in teaching.

At first glance, this all seems commendable. After all, the goals have laudable aims and who can disagree with ending poverty, tackling climate change, or providing clean and affordable energy? But there are numerous problems with fetishizing the SDGs in this way. Most notably, the SDG grid (or wheel) operates as a sort of pious palimpsest that obscures the destructive dynamics of neoliberal capitalism and the realities of power. As such, it diverts teachers’ and students’ attention away from analyzing these dynamics and the need for systemic reform and a just transition. Moreover, the underlying conception of the SDGs maintains the simplistic fiction evident in official sustainable development discourse since the Brundtland report. This is the fiction that economic growth (SDG 8, which Biermann notes is often cited by multinationals to justify their operations) can be combined with climate and ecological action. Another serious problem is that climate action is very low on the list, at SDG13, and is just one of the seventeen goals. This dilutes the gravity of global warming and defuses the urgency of radical emissions reductions. Finally, at an institutional level, because the SDG grid covers so many issues, it enables universities to claim a commitment to sustainability by adopting a tick-box approach to mapping existing teaching without actually reforming the curriculum in any serious way.

There are many ways that using active pedagogies in teaching can mitigate some of these (and other problems) with the SDG-centred ESD approach. Nonetheless, the increasing dominance of this approach should cause alarm. The way SDG talk is permeating higher education is effectively socializing young people into a technocratic discourse and way of thinking that has been shown to be inadequate. Moreover, the power of this legitimating discourse is such that it continues to entangle even the experts who have demonstrated the SDGs’ failures. Despite his findings of all talk and no action, Biermann, for example, cannot bring himself to suggest substantial reforms, calling instead on “civil society and social movements to prick the bubble of SDG talk”.[12] The recommendations of the 2023 independent SDG review panel are even weaker, as the title and strapline of their Nature article show: “What scientists need to do to accelerate progress on the SDGs. Drilling down into why the UN Sustainable Development Goals are so hard to achieve will help the planet and save lives.”[13] Notably, neither set of experts even mention neoliberalism, never mind the critiques that have been around for at least eight years. It is in this context that more radical approaches to sustainability education, which foreground neoliberalism and climate-ecological crisis, are urgently needed.

2. Developing an Education for Sustainability (EfS) Approach: Three Sources of Inspiration

The EfS approach I developed between 2012 and 2014 was motivated by several converging factors. The first was the epiphany I experienced during a seminar by climate scientist Kevin Anderson in 2007. Until then, like most people in the UK at the time, I knew little about global warming. But I left that seminar in no doubt about the gravity of climate change and the urgency of emissions reductions and a zero-carbon transition. It was also a catalyst for refocusing my research on UK climate policies and grassroots sustainability initiatives. The second factor was the realisation that there were serious gaps in students’ interests and the wider curriculum. My interdisciplinary studies students invariably chose dissertation topics relating to social justice, but showed little concern for environmental issues; and none of the few environmental modules scattered across departments focused squarely on climate change or sustainable solutions. The third factor was the shift in UK public debate around climate change after 2010.[14] Whereas there had been a cross-party consensus around New Labour climate initiatives between 2006-10, this quickly broke down when the Liberal Democrat-Conservative Coalition took office. The Coalition not only brought in a host of “austerity” policies cutting public services and social benefits. Chancellor Osborne also cut a swathe of carbon-reduction policies and sustainability initiatives, reframing them as “green taxes” and thereby amplifying and legitimating climate sceptic discourses.

In this context, it seemed increasingly urgent to get climate and sustainability modules into the curriculum. The challenge was: what could I actually teach? When I began looking around, it became clear that colleagues elsewhere were also grappling with this issue. The Higher Education Academy, the national body for sharing best practice, for example, had set up the Green Academy in 2008 to help develop teaching in this area. But most of the pilots seemed related to more vocational degrees, so although I noted the common use of active pedagogies, they were of little help conceptually. That’s when I started reflecting on the lessons from my research and teaching on the role of education and social movements in transitions from authoritarian rule to neoliberal democracy in Latin America and Taiwan. These reflections led me back to Paolo Freire – whose pedagogies had been crucial to grassroots literacy campaigns and popular mobilisation in Latin American transitions and also influenced the education reform movement that played an important role in the transition from military rule in Taiwan.[15]

In his 1968 classic Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Freire outlines the core principles that underpinned his life’s work. He starts from a critique of dominant transmission and “banking” pedagogies, based on a standardised, top-down curriculum, rote learning and authoritarian relations between teachers and students, which he views as legitimising and inducing conformity with the status quo. He proposes instead that “revolutionaries” start where students are and investigate how they are conditioned by dominant ideologies, relations of power and material realities. This is a call to humility regarding the very real oppression and educational marginalization suffered by the poor in Latin America at the time. It is also crucial for establishing a baseline for the next phase: consciousness-raising, which is grounded in the principles of “denounce” through critique and “announce” possibilities for change and action. In contrast to transmission methods in which teachers tell and expect students to absorb, in the process of consciousness-raising teachers work in more horizontal, dialogic ways to enable students to reflect on, read, and name the world and thereby become actors able to exercise voice in politics and society.

I had always admired Freire’s work. But these principles took on a new relevance in relation to the neoliberalization of education in the UK. This process was still incomplete in universities ten years ago. But it was alarmingly clear in schools – evident in institutionalized competition, teaching to the test, and reduced spaces for teachers and students to exercise creativity and autonomy. Moreover, the impact of neoliberal conditioning was becoming discernible in the orientations, values and practices of students arriving at university. In this context, my concern about students’ lack of environmental knowledge was compounded by the sense that due to their conditioning new cohorts were increasingly ill-equipped to think beyond the status quo and tackle the challenge of climate change. Re-reading Freire strengthened my conviction about the urgency of getting climate into the curriculum and made me reflect on how to address the neoliberal common-sense I was hearing in classes. It was also a catalyst for reconceiving education in the UK as a site of climate activism and reorienting my stance from researching/teaching about transitions to researching/teaching for a transition. However, whereas critique and active pedagogies were central to my teaching, I was less sure how to “announce” the possibilities for change. It was here that a second, complementary source of inspiration was very important.

This second source of inspiration came from the practical, solutions-oriented research and pedagogies developed by the Centre for Alternative Technology (CAT), a pioneer of sustainable innovation and education in the UK since the mid 1970s. I first became aware of CAT’s educational work in 2011-12 when I met several graduates from their MSc programmes who were organising community sustainability initiatives in Bristol.[16] I was impressed by how knowledgeable they were about climate change, different aspects of sustainability, and their high levels of motivation and commitment to social engagement. At the time, I was vaguely familiar with the history of CAT, which was set up as an exemplary sustainable community on the site of a disused quarry in Mid Wales in the context of the oil crisis and growing alarm about peak oil and environmental limits.[17] But the way they had stepped up their research and expanded into formal education since the late 1990s in response to the climate and ecological crisis was a revelation – especially when compared to the incipient state of sustainability education in universities.

- Hard facts of the climate and ecological crisis

- Inspire hope: macro-level strategies & solutions are feasible (Zero Carbon Britain)

- Inspire action: testimonies from activists and social entrepreneurs

- Experiential learning at CAT

- Equip with skills: project work and dissertations

Figure 2: Pedagogical sequencing of Sustainability MScs: Centre for Alternative Technology

CAT’s flagship research project, Zero Carbon Britain (ZCB), launched in 2007, proved to be crucial. It models the policy changes needed in energy, homes and buildings, transport, food and agriculture for a rapid transition, while exploring “the potential barriers and how they can be overcome”. Written for non-specialist readers, the ZCB reports enabled me to grasp the scale and dimensions of the transformations required to transition away from fossil fuel dependency. They are also valuable resources to use in teaching.[18] The pedagogy underpinning CAT’s MScs, which address subjects like sustainable architecture, urban planning and energy, was equally instructive. These unconventional degrees, with students attending intensive, week-long residential modules spaced over a year or more, are specifically designed to equip graduates to become change-makers and many go on to jobs in local government and NGOs. The ethos is summed up by CAT’s motto: “Inspire, Inform, Enable”. But the most important pedagogical lesson from interviewing CAT staff and graduates was that sequencing is key (see figure 2). To paraphrase one graduate, they hit you with the hard facts of climate change right at the start of the course and then inspire and motivate you to do something about it by focusing on solutions and by inviting activists who have set up new sustainability initiatives to give guest lectures.

The third source of inspiration that was helpful in developing an EfS approach was Naomi Klein’s 2014 book, This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs the Climate.[19] As discussed above, I had tracked the deepening hegemony of neoliberalism since the 1980s and was already aware of the incompatibility between neoliberal orthodoxy and climate action. However, Klein sets this out in a clear, straightforward way that is accessible to students. In Part 1, “Bad Timing”, she argues that tackling the climate crisis requires the re-deployment of government subsidies, public investment and incentives, as well as new policy, regulatory, and legal frameworks, based on the precautionary and polluter pays principles. But, as Klein emphasises, just when scientists were raising the alarm about climate change in the late 1980s, neoliberals were rolling back the state and promoting libertarian free market policies and de-regulation. Just as significantly, based on her interviews with libertarians and observations of right-wing conferences between 2010 and 2013, Klein stresses that the neoliberal right are not going to give up their hegemony easily. They prefer to live with climate change than allow the state back in and jeopardise the “freedoms” they have achieved.[20] Given these findings, she concludes, calling on neoliberal governments to act decisively to tackle the climate crisis will fail. Instead, it will be up to grassroots social movements to block the expansion of extreme energy and other ecologically damaging projects and form coalitions to push for a just transition and a reconstruction of social democracy that will tackle both the social and environmental crisis.

Put simply, one of the great strengths of This Changes Everything is that Klein historicises neoliberalism, challenges the slogan that “there is no alternative”, and answers the common-sense question frequently heard at the time it was published: “if climate change is so important, why aren’t governments doing anything about it?” Moreover, because she highlights the importance of social movements and alternative political projects in any transition to a zero-carbon society, her work complements CAT’s pedagogical approach.

3. Designing EfS Modules and Initiatives

Finding space in an established curriculum for climate and sustainability teaching can be difficult and often involves a lot of lobbying. In the Interdisciplinary Studies Centre where I teach, degrees are organised with a core course in each year and students take options from departments across the social sciences and humanities. So, although my then head of department was sympathetic, resource constraints meant there was little prospect of getting agreement for a new module. The opportunity when it came was in the unlikely guise of employability. This became a compulsory strand of the university curriculum in 2014 in response to government demands for education to serve the labour market and new HE performance metrics. As I was well aware, this emphasis on employability was indicative of the erosion of humanist values and the increasing instrumentalization of education. Nonetheless, it opened up curriculum space and, paradoxically, provided the creative constraints that enabled me to find a form for the approach I had been mulling over. Figure 3 shows the design of the resulting 15-credit module, CS200 Social Entrepreneurs, Sustainability and Community Action, and how I adapted the insights derived from Freire, CAT and Klein within these constraints.

- Introduction to the Co-operative & Social Enterprise Sector

- Changing State-Civil Society Relations & Social Inequalities since 1945

- Neoliberalism, the Climate-Biodiversity Crisis & Emerging Paradigms for Change

(e.g. ZCB, Green New Deal, Degrowth, Circular Economy)

- Co-operatives (Guest Talk + Mondragon & other cases)

- Organizations Acting for Sustainability: Group Case Study Research & Presentations

(e.g. Woodland Trust, SUSTRANS, Low Carbon Hub, CAT, etc.)

- Alternative Wealth Creation in Local Economies: the Cleveland/ Preston Model

- Mutual Self-Help & Learning from Models of Good Practice

- Identifying Needs, Sources of Funding & Project Design

- Becoming a Social Entrepreneur

- Group Tutorials: Ideas for Final Sustainability/ Social Project or Social Enterprise

- Final Workshop: (Draft) Project Presentations

ASSESSMENTS: 1. Group research & case study presentation; 2. Reflective Essay; 3. CV & Application for Internship; 4 Individual Project Presentation; 5. Written Project Proposal: Small-scale Sustainability/ Social Project or Social Enterprise

Figure 3: CS200 Social Entrepreneurs, Sustainability and Community Action

CS200 Social Entrepreneurs, Sustainability and Community Action was a pedagogical experiment that took me into a new teaching area, so the enthusiastic engagement of the small pilot cohort was a relief. Equally important, the pilot enabled me to find out if my perceptions of gaps in students’ knowledge and understanding were justified. In this regard, the reflective essay, which students write after week seven, was particularly valuable. Reading these essays is a way to gauge what students have learned and enjoyed, and over the years, the main themes have been remarkably consistent. Before the module, few have studied climate change or have any knowledge of neoliberalism, and most know little about social enterprises and cooperatives. Of the alternative paradigms, they invariably discuss the circular economy, suggesting it is easier to grasp than degrowth or the Green New Deal. Another insight from their essays is that most students really enjoy the group case study research and presentations. They frequently express surprise at the number of organisations working for sustainability, and say this gives them hope and makes them feel more optimistic about the future. It is also worth noting that the creativity and high quality of many of their final projects often exceeds their and my expectations.[21] In terms of longer-term impacts, one indicator is that more students are going on to do climate/environment related dissertations and Masters’ degrees.

Due to the success of the pilot, CS200 became a permanent part of our interdisciplinary studies curriculum – although it is only compulsory on some degrees – and two years later I was asked to design a follow-on final year option. This became CS300 Community Engagement: Sustainability Group Projects, which has a practical orientation and uses learning through discovery and doing (based on how much CS200 students benefitted from these). I have also used the flexible pedagogical scaffold derived from Freire, CAT and Klein to structure other small-scale EfS initiatives and public talks. The most notable is the Summer School in Sustainable Practice, which is now in its sixth year.[22] As Figure 4 shows, one of the strengths of the framework is that it can be re-oriented and updated according to the particular aims of the course or talk.

- Understanding the Climate & Biodiversity Crisis; Beyond Neoliberalism & “Sustainable Development”

- C20th High Modernist Development, Regenerative Agriculture & Resilience

- Fieldtrip & Vegan Lunch: Bennison Organic Farm CSA

- Ecoliteracy, Conservation, and Rewilding

- Fieldtrip: Essex Wildlife Trust, Fingringhoe Reserve

- Towards Zero Carbon Energy, Transport, Homes and Buildings

- Acting for Change on Campus

- Group Projects

- Project Presentations and Closure

Figure 4: Summer School in Sustainable Practice 2023

Conclusions

Ten years after she published This Changes Everything, Klein’s prediction about neoliberal resistance to climate action has proved remarkably accurate – and has also become relevant to libertarian populism. The denial, delays and rhetoric of successive UK Conservative governments are a textbook case. Moreover, far from implementing the SDGs on ending poverty or reducing hunger and inequality, the Conservatives have cut overseas aid; and, domestically, austerity policies have dramatically increased precarity, hunger and the use of food banks. In terms of policy, we still haven’t had a public education campaign; and the Department for Education’s 2023 token initiative for schools resisted campaigners’ calls to systematically integrate climate education into teacher training and the national curriculum. Consequently, most students are still arriving at university with little knowledge about climate change and unaware of positive sustainability initiatives. At the same time, students’ material conditions have deteriorated due to the fees hike and the inadequacy of the loans regime and many are working long hours to fund their studies. This means they have little time or energy for extra-curricular activities, including political engagement, and the anxieties of living in precarity are compounded by a diffuse sense of climate doom. Given this context, higher education has a crucial role in climate and sustainability education. Many UK universities have declared a climate emergency and there is more environmental research and more environmental modules in the curriculum than ten years ago. But with a few exceptions, integrating climate and sustainability teaching into the compulsory core curriculum remains an urgent task. Within such teaching, as I have argued here, it is important to include some discussion of neoliberalism, whether in its classic or populist form, and to inspire hope by making visible both the possibilities for change and those that are already occurring.

Footnotes

[1] A big thank-you to the organisers and participants of the ISRF conference “Climate Crisis, Global Capitalism and Higher Education,” November 2023, for a very stimulating, convivial event.

[2] Richard Schaull, “Foreword,” in: Paolo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, transl. M. Bergman Ramos (New York 2000 [1972]: Bloomsbury): 29–34, 34.

[3] Jason Hickel, “Five Reasons to Think Twice about the UN Sustainable Development Goals,” LSE Africa Blog, September 2015, available at: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/africaatlse/2015/09/23/five-reasons-to-think-twice-about-the-uns-sustainable-development-goals/

[4] Frank Biermann, “UN Sustainable Development Goals Failing to Have Meaningful Impact, Our Research Warns,” The Conversation, June 2022, available at https://theconversation.com/un-sustainable-development-goals-failing-to-have-meaningful-impact-our-research-warns-185269.

[5] UN Department of Social and Economic Affairs, “World risks big misses across the Sustainable Development Goals unless measures to accelerate implementation are taken, UN warns,” July 2023, available at https://www.un.org/en/desa/world-risks-big-misses-across-sustainable-development-goals-unless-measures-accelerate; United Nations, The Sustainable Development Report 2023: Special Edition (2023), available at https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2023/?.

[6] Shirin Malekpour et al., “What scientists need to do to accelerate progress on the SDGs,” Nature 621, no. 7978 (2023): 250-254. This evaluation was commissioned by the UN.

[7] Hickel, “Five Reasons.”

[8] Biermann, “UN Sustainable Development Goals.” Biermann and his team reviewed over 3,000 articles related to the SDGs.

[9] UNESCO, Education for Sustainable Development: A Roadmap (Paris 2020: UNESCO). Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374802.

[10] See, for example, Stephen Stirling, Sustainable Education: Re-visioning Learning and Change (Dartington 2001: Schumacher Society). This was the “manifesto” that shaped his subsequent publications.

[11] UNESCO, Education for Sustainable Development, 22.

[12] Biermann, “UN Sustainable Development Goals.”

[13] Malekpour et al., “What scientists need to do.”

[14] There had been some important action on climate change under New Labour between 2006 and 2010, including the Climate Change Act and support for grassroots sustainability initiatives. But their plans to scale up carbon-reduction and sustainability initiatives, launch a public education campaign and to integrate climate and sustainability into the national curriculum were dropped by the Coalition.

[15] Ming-sho Ho & Jane Hindley, “The Humanist Challenge in Taiwan’s Education: Liberation, Social Justice and Ecology,” Capitalism Nature Socialism 22 no. 1 (2011): 76–94.

[16] Jane Hindley, “Bristol Green Doors: Promoting Home Energy Retrofitting, Combatting Climate Change,” in: S. Böhm, Z. Pervez Bharucha & J. Pretty (eds.), Ecocultures: Blueprints for Sustainable Communities (Abingdon 2015: Routledge): 164–179.

[17] As their website recounts, CAT’s founders included “engineers, architects, builders and growers” and they gained a lot of media attention when they set up the centre. In the 1970s and 1980s they promoted renewables and low-carbon living through short courses and their visitor centre and their technical initiatives included experiments with solar and wind generation, as well as solar fridges, clean cook-stoves, and low energy buildings. See Centre for alternative Technology, “History,” available at: https://cat.org.uk/history-2/.

[18] There have been four main Zero Carbon Britain reports since 2007: Zero Carbon Britain: An Alternative Energy Strategy (2007); Zero Carbon Britain 2030: A New Energy Strategy (2010); Zero Carbon Britain: Rethinking the Future (2013); and Zero Carbon Britain: Rising to the Climate Emergency (2019). In tandem with the reports, CAT provides numerous resources on their website and runs training courses and workshops for local authorities and communities.

[19] Naomi Klein, This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs the Climate (New York 2014: Simon & Schuster).

[20] Ibid., 38–46.

[21] The final projects are required to identify and address an actual gap in existing provision and/or services in a specific place: they range from community gardens, local sustainable transport and food waste schemes, to converting a derelict building into a zero-carbon hub for social enterprises.

[22] This intensive, extra-curricular course provides 25 places for Essex students from all disciplines and levels of study, free of charge. It is held in the last two weeks of the Summer term.

Biography

Jane Hindley is a Senior Lecturer in Interdisciplinary Studies at the University of Essex. Her early research focused on indigenous mobilisation, social movements and regime transitions in Latin America. But for the last 15 years she has been researching UK climate change policies and grassroots sustainability initiatives. Jane also has particular expertise in education for sustainability (EfS). As well as developing and teaching EfS modules, she has been involved in a range of community outreach initiatives (including with local primary schools) to raise awareness of climate change and to promote ecological and sustainability literacy.